Cross-domain collaboration

Building great systems requires more than great system builders

Making digital products requires both technical and non-technical knowledge, which presents a big challenge. In this article, I will first elaborate on that challenge, then explain what the difficulty is with talking about ‘business’ and ‘IT’, before finally explaining my view of working together optimally with multiple knowledge holders. To illustrate my story, I will refer to a fictional company that makes software to file taxes: TaxFile, Inc.

TaxFile has around 300 employees and a single mission: to make filing your taxes less of a hassle. In order to be successful, TaxFile needs a lot of experts to cover many fields of expertise. Of course, there are the departments that lay the foundation to do business, like finance, human resources, and marketing. But building the core product is a multi-domain pursuit as well, as knowledge of accounting, fiscal law, and building software is needed.

Herein lies a challenge for TaxFile. In a perfect world, they would want to find accountant-lawyer-developers that could build software that is easy to work with for the customer, while also making sure all rules and laws are complied with. Unfortunately, there are not many accountant-lawyer-developers to choose from.

So, TaxFile does what every company does: find people that are experts in one of these fields, and bring them together. They have a department of accountants, a department of fiscal lawyers, and a department of software developers.

Unfortunately, TaxFile finds what every company finds: bringing these disciplines together is not trivial. Sure, all the knowledge to build good software is under their roof, but that alone is not enough to guarantee good software. The software will only be as good as the collaborative process in the organisation.

‘Business’ vs. ‘IT’

In a corporate setting, just like in the rest of the world, humans are tribal. This can lead to an “us vs. them” mentality quite quickly. At TaxFile, development teams often mention ‘the business’, which can mean anything depending on the context. Sometimes, ‘the business’ is a project group, sometimes it refers to everyone outside of delivery teams, sometimes it is anyone who does not produce code at work, and sometimes it is anyone that is not the speaker.

I think there is a risk to classifying some people ‘the business’. It implies that others within the organisation are not (part of) ‘the business’. This creates a division (us vs. them) and blurs who has responsibility for a topic. Both are inherently bad if we want to achieve things together. The business is everyone working on it, not a subset. If the business is not providing you with something, it helps to specify who within the business is needed to help you out.

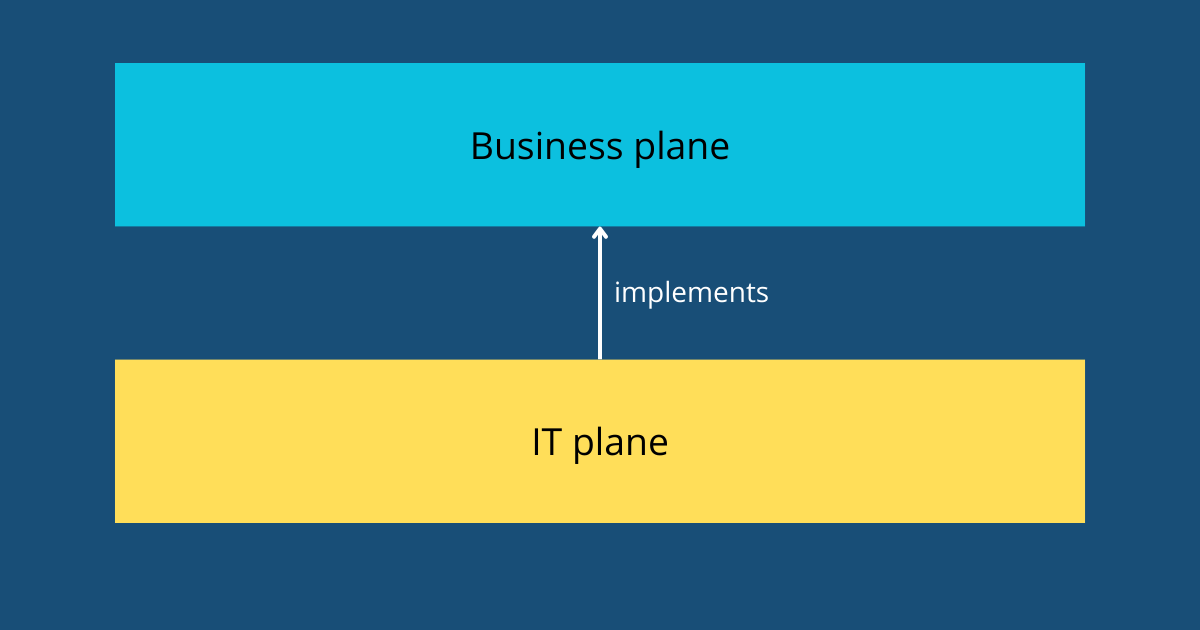

Similarly, classifying ‘IT’, usually to reference development teams, is overly simplistic and not supportive of good collaboration. Information technology is not an end but a means, and systems should achieve business goals. Of course, some people could be classified as working in IT, and in some contexts that makes sense. But what about a product owner or product manager: are they part of IT, just because they are teamed up with developers?

Looking at development teams as just IT, clouds what they are actually attempting to achieve. If we then also classify a ‘business’, it becomes clear that the company is splitting up the thinking work and the building work. This is a recipe for misaligned outcomes that do not satisfy the requirements of all domains involved. This is silo-thinking at its finest.

Of course, we can distinguish business-level capabilities, and there are people responsible for information at this level. But talking about ‘business’ in this sense is too vague In TaxFile’s example, ‘business’ could concern accounting or legal questions, requiring vastly different skillsets. If you need something from anyone that operates at the business level, you will have to specify who, or risk not getting what you need.

Similarly, talking about IT is not clear enough. The IT plane is always in service of the business plane, as illustrated below. While the work may be technical, it serves to enable something on the business plane, so it is not recommended to separate these worlds too much: that is a recipe for misaligned outcomes that do not satisfy the requirements of all domains involved. Silo mentality1 at its finest.

Bringing knowledge together

Now that I have clarified my view of the relationship between business and IT, the question becomes: how do we make sure these planes come together optimally?

Collaboration means tackling problems together with the people that have the required expertise. In TaxFile’s case, they would do best to put a lawyer, an accountant, and some software developers into one room. A product manager or owner can lead this newly formed team and propose an idea to improve the product TaxFile builds. From their own expertise, the lawyer, the accountant, and the developers will refine the solution to the problem, to make sure it is optimally coherent with their domain knowledge. By having immediate access to the knowledge needed to confirm or refute assumptions, the team can move on quickly.

Once the lawyer and the accountant are in the room with the developers, do not be too quick to let them out. By fostering close collaboration between all the relevant knowledge holders in an organization, the end product improves. Keep the knowledge away from the people building the solution, and that solution will be suboptimal. Teams with diverse knowledge backgrounds can work more independently than homogeneous teams. When development no longer requires intensive help from either the accountant or the lawyer, they can leave the team once again.

In practice, I find that it makes the most sense to organise people around value, a phrase I read in the book Team Topologies2. It means getting the parties together that can create something valuable for customers, and no one else. Try to find the simplest form of this that allows for much communication: putting people together in a team (preferably co-located!) gets things done much quicker than a project with a weekly update meeting. If joining the team is not possible for all knowledge holders, at least guarantee that interaction is easily available. Besides aiding in building the product right, quick and effective interaction breeds a feeling of responsibility for each contributor’s own expertise. It is no secret humans perform better when they have the feeling they have something to contribute, and moving forward quickly is good for the team’s morale.

In larger collaborations, it may be useful to employ analysts or project managers to coordinate information flow between parties and improve collaboration, but this should only be done when there is an explicit need, not just because ‘a project needs a manager’. Remember, keep it simple.

To conclude: TaxFile has the biggest chance to build software that actually solves a problem if they get the right people close together and communicating easily. Collaboration is a multiplier in organisations: if you do it wrong, you will get less done. If you do it right, however, and enable teams, they can get more done than any of its members could do individually. Doing it right mostly consists of getting the right pieces of knowledge to find each other quickly. And do not just call for ‘the business’ or ‘IT’ to help you out: specify who is needed!

I’m curious to hear your take! Please share any thoughts you have on this article

Additionally, if you’d like to read my future work, considering subscribing to be notified when I post new findings.