Ever wondered why business transformation can be so difficult? As a full-time business analyst, my job is to clarify three things:

A map of the present (Now)

A clear image of the future (Next)

A path to get from Now to Next

This sounds simple, but it’s not. Each step can be challenging, especially in large organizations where many things happen at once. As a consultant, I am not usually the subject-matter expert in the companies I work at. This makes it difficult to get a grip on all the details.

In this article, I will share some observations on the troubles I find in changing a business. A central idea that I often mention: IT is business, and most businesses are IT. Understanding business well helps you create better solutions. Understanding the IT really well is also important, but may be useless without a clear business purpose.

The three-step plan I set at the start is a recipe for business change, and I will expand on it in this article. By understanding how to get to the Next, we can understand business transformation.

1. A map of the present (Now) 🗺️

Any journey must start by knowing the current position. On a hike, this means checking the physical map, trying to find points of recognition and figuring out which way is North.

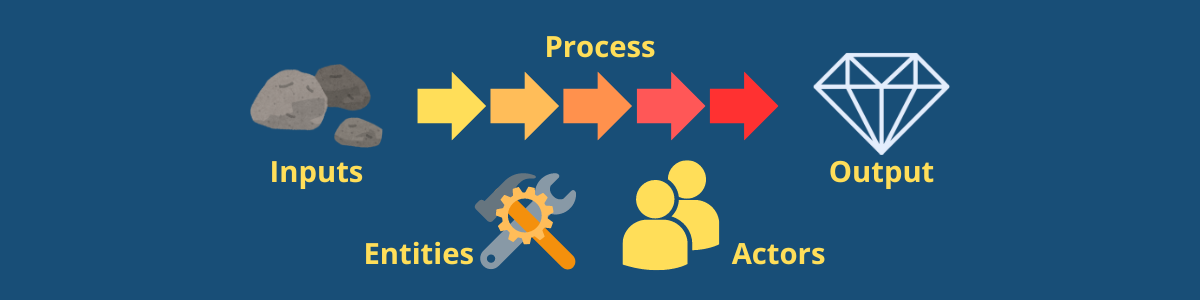

In business, the process is similar but more complex: we must understand which actors, entities, and processes lead to value creation. Interestingly, it may be the case that no one truly understands all aspects. Big businesses do not become successful by accident: successful businesses just become bigger, growing in complexity and making it vague what the key factors are for creating value. As I alluded to in my plea for deliberate simplicity, complexity slows down the business by increasing cognitive load for all those involved. Keeping a grip on complexity is a must for keeping the business running.

To understand where we are, we must map the three mentioned key elements:

Actors are both internal to your company (employees having roles) and external (customers(!), suppliers, partners).

Entities are the non-human parts that play a role in the business. This spans a wide range of things, from technology to contracts.

Processes take inputs and transform them into outputs by interaction between actors and entities. If done right, this transformation creates value. That is what customers pay a business for. If the output is more valuable than the input, the business is independently sustainable. Actors and entities interact within processes to create value.

It can be difficult to establish a map of all these matters in a business that has never paid attention to this. After mapping these elements, however, anyone that knows the business should understand the maps. Employees that execute the process will be able to see whether your process map makes sense and if any actors are missing. Engineers will be able to explain which entities are part of the code, and subject matter experts will be able to tell you if those make any sense in the business context and if the interactions are correct.

Which techniques you use for this mapping does not matter that much, provided they are simple. If you need a separate degree to understand what is written, it will lose its value of global understanding, which is exactly the value we are striving to get. Opt for something simpler, or add quick instructions. As an example, I am a big fan of BPMN1 for process maps, but will add some context if any non-obvious events happen or if an event is non-interrupting. Additionally, the entities (and actors) are best captured in a simple entity relationship diagram2 (ERD). These diagrams often consider the actors to be entities as well. I have separated the two because people require vastly different approaches and techniques than objects.

2. A clear image of the future (Next) 📍

Knowing where we are is a great first step, but it needs to be followed up by knowing where we are going. I like to call this Next. The future state or target state are also names for this, but I prefer Next as it shows clearly that this will not be the last state the business will be in. That is because it rarely ever is the final station - healthy businesses move the goal posts when they are near, so that they can keep going and keep growing.

Next is distinctly different than Now. Now already exists, so it is ‘merely’ a matter of (re)discovering which cogs are in the machine and how they turn. Next does not yet exist, but must be shaped. This shaping is not a trivial process. It requires business leadership to set a course, and with that, also choose not to set other courses. The Next can have more than one goal in it, but it cannot have hundreds, because it will become impossible for the organization to apply focus to those goals.

Next does not have to be a whole map of the new business immediately, but it must be a clear quantifiable goal. If it can be quantified, it can be satisfied. Vague goals, however, will not guide employees effectively.

KPIs and OKRs can be used to quantify goals, but the technique is not the most important thing. We must simply know where the organization is going and when we have arrived. How the exact organization looks when that is done, is not yet where the focus needs to be. Making such predictions is often too hard and time-consuming.

Especially in larger organizations, where the Next is quite far away as well, it is a good idea to set a clear North Star3 that all initiatives can be measured against. For example, if the North Star is to become less dependent on a single supplier, this could be quantified by making sure no supplier is involved in more than 40% of the sales. For each new initiative, the business can ask: is this initiative increasing positions of our small suppliers or decreasing the position of our biggest supplier? If the answer is yes, the initiative can be pursued. If the answer is no, maybe we should consider other options.

3. A path to get from Now to Next ➡️

If we know where we are and where we’re going, then the route can be decided by analyzing the gap. What are the differences between our current situation and a situation in which we achieve these goals? By performing a gap analysis between the actual state of the business and the projected future, we can build towards the Next.

Because we have spent time on defining where we want to go, we can estimate whether new ideas, projects, and products contribute to this. In our previous example, a project that makes the biggest vendor have an even bigger influence may not be the best way forward. The negative (this will not work for us) can sometimes be concluded just by seeing if the initiative’s expected outcome aligns to the Next state.

The positive (this will work for us) however, is not always that obvious. Even if the expected outcome aligns, that does not mean yet that the actual outcome does as well. In complex contexts, this is where an agile way of working makes sense. Build iteratively, see if the results you have are in the right direction, adapt based on those results.

Finding initiatives that align is not enough; we should prioritize those that will have the largest impact. Of all of the changes that will need to happen to go from Now to Next, which ones will have the most impact on the goals we have chosen? Start with those. Prioritizing big impact changes will both lead to great business outcomes and give much more insight into how good the Next actually is. After making changes, their impact can be analyzed in order to see if the way you’re going actually is right.

In conclusion, making meaningful impact requires:

Knowing where you are

Knowing where you want to be

Having a well-thought-out plan of going from the former to the latter

Even with these ingredients, creating positive business change is challenging. Trying to achieve good business outcomes without them will likely leave you and your stakeholders frustrated and stagnant.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this recipe. I’m curious to hear if you can apply it in your work.

As described on https://www.omg.org/spec/BPMN/2.0/

As explained on https://www.lucidchart.com/pages/er-diagrams

As described by Roger Burlton in his book Business Architecture