Uncertainty and estimation

Predicting the future

Is planning a software development project the same as looking into a crystal ball? To some extent, yes. Planning is predicting the future, and there is significant value planning accurately. If we can anticipate what the future holds, we can optimize future returns. This idea is so compelling for many organizations that they invest significant effort in planning better and becoming more predictable. At the same time, the complexity that many organizations work in makes true predictability a challenge. Planning, especially when done far in advance, is assumption-driven and therefore often inaccurate. How should we balance the inherent unpredictability of complex work with the average enterprise’s desire to plan ahead? And how much time should we spend refining work to increase predictability and plannability? Let’s explore both sides of the balance before deciding how must be struck.

Unplannable work

By their definition, complex problems (as defined within the Cynefin framework1) cannot be fully anticipated in advance. In complex contexts, deviations from the plan are inevitable as time progresses. In DevOps teams, a major incident or revisiting a change after gathering feedback are expected events. The premise of agility is that we don’t know what will end up working and as such must prepare to change our plan as soon as we find out. Plans can be made, but they should be outcome-oriented and short-term.

Even static work can be hard to plan. This is because knowing what to build does not always translate to knowing exactly how to build it. If the software landscape is well-thought-out and the change request is simple, we can get close. However, if systems are sufficiently big, even slightly complicated changes become unmanageable. Other work that requires the same developers’ capacity may also take longer than expected, impacting the timeline of a seemingly unrelated change. Additionally, developers are human, meaning their performance can vary from day to day based on external factors. A bad night’s sleep or something exciting happening in a developer’s personal life can lead to lower productivity on a given day.

Refinement

Teams refine in advance to varying degrees, depending on the change. Refining work beforehand is useful for planning and fostering shared understanding. It must be noted though that technical refinement is an activity that requires the same people as development. This takes time away from development, investing it to provide a degree of certainty. While refinement can provide valuable insights, the returns diminish over time. If too much time is spent upfront, it might have been easier to tackle the change directly. We must not get lost in an analytical search for certainty, because we cannot know what will happen.

The need for planning

The benefits of planning for an organization are numerous. Knowing what is coming up gives a sense of control, and allows orchestration of all the different activities happening in the organization. As an example, it is generally wise not to do a mission-critical release on Christmas eve, or update the accounting software two weeks before the fiscal year ends. Furthermore, how long something will take (and when it is done) can be a factor in deciding what to do - if you cannot deliver before the competition, you may put your focus elsewhere.

Understanding what lies ahead, rather than living day to day, is essential for business. Dismissing planning by citing the Agile manifesto and claiming it is impossible - or worse, “not Agile” - is not an option.

A balancing act

In deciding the balance between these perspectives, I often find myself coming back to the following quote by U.S. President Eisenhower2:

“In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable”.

- Dwight D. Eisenhower

Although the context of this quote is military, it applies to business generally. Planning, exploring options, and mapping terrain are incredibly useful for tackling problems and making changes. However, by definition, emergencies are unexpected, meaning that the plan will never be a perfect fit (or else there would not be an emergency). We thus treat plans as a way to explore what we expect to be spending time on, while accepting that we may need to deviate and should not hold on to the plan.

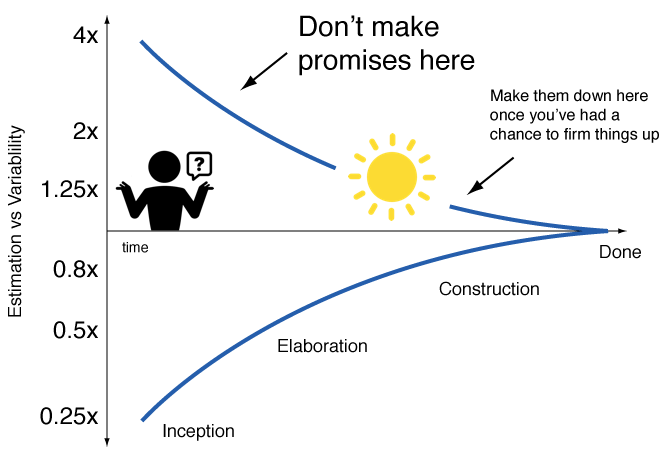

Estimates we set must not be confused with definitive timelines. The further we look ahead, the broader our planning should be, as the cone of uncertainty3 below shows. If we are planning far ahead, estimations should be rough order of magnitude (rather a range of 3-6 months than 4 months) to show in the estimate that it is not ready for precise timeline planning. Once we get down to the details (such as a single backlog item), we can say with more confidence how long it will take, though never forgetting that unexpected events may still happen and that the same people are needed for most of the team’s work.

Reviewing planning capabilities can also be useful to a degree. If we consistently overpromise, then it is a good idea to course-correct. The same goes if we do more than we have indicated some time ago. There is nothing wrong with estimating what you can do in the future, as long as it is clear that reality can deviate from those estimations. Completely eliminating planning and allowing teams to operate without accounting for the world around them is unproductive in most organizations. However, we can ensure that our estimations remain realistic and modest. If your annual roadmap must be followed exactly in order for the company to survive, this suggests a deeper problem. Consider increasing the planning frequency (thereby reducing the timeline) to maintain better control. Additionally, be careful not to over-plan to the point where it leaves insufficient time for development. Ultimately, the art of planning lies in striking the right balance between foresight and flexibility, ensuring that teams are prepared for whatever the future may hold.