Language matters

Choosing the right words at the right time

While working on a process that required one (unlucky) operations employee to scan documents all day and upload them to a portal, I named that role ‘unlucky scanning professional’ on the fly (roughly translated from the Dutch word scansjaak). About a week later, to my surprise, this playful working name started appearing in official project documentation! After a few seconds of worry and a quick phone call I was able to get some documents changed, but the name I thought of within a second remained used in all refinement sessions we had thereafter regarding the topic.

This incident taught me that language can quickly evolve through its users and be unpredictable and confusing if not managed and considered carefully. While this unpredictability was fine during our informal refinements, it could become a major obstacle if definitions become blurry.

A common language enables communication, and communication enables collaboration. It follows that in order to collaborate (effectively), we need a common language. And finally, we need effective collaboration to achieve our business goals. Although I often state the blatantly obvious in my articles, this point may take the crown. Still, I am of the opinion that many organisations have room for major linguistic improvement. How common should the common language be? And how do we make it easy for everyone to adhere to the common language?

A language is a living thing that changes to accommodate the expressive needs of its speakers. As new technology is invented, language changes around it, either with new words or by expanding older ones. To illustrate, the concept ‘steam engine’ was not needed until the steam engine was invented, and in 2005 a programmer mentioning a ‘cloud’ was much rarer than it is now. While natural languages are more difficult to manage than contextual business language, you may still face difficulty maintaining control of the language used within your team or department.

Language management is not a solved problem and while I have some ideas, I am also still exploring how to work with domain language within organisations. There is one element that is important for me to mention: the use of technical language. Additionally, I will share some of my thoughts on language management.

Technical language

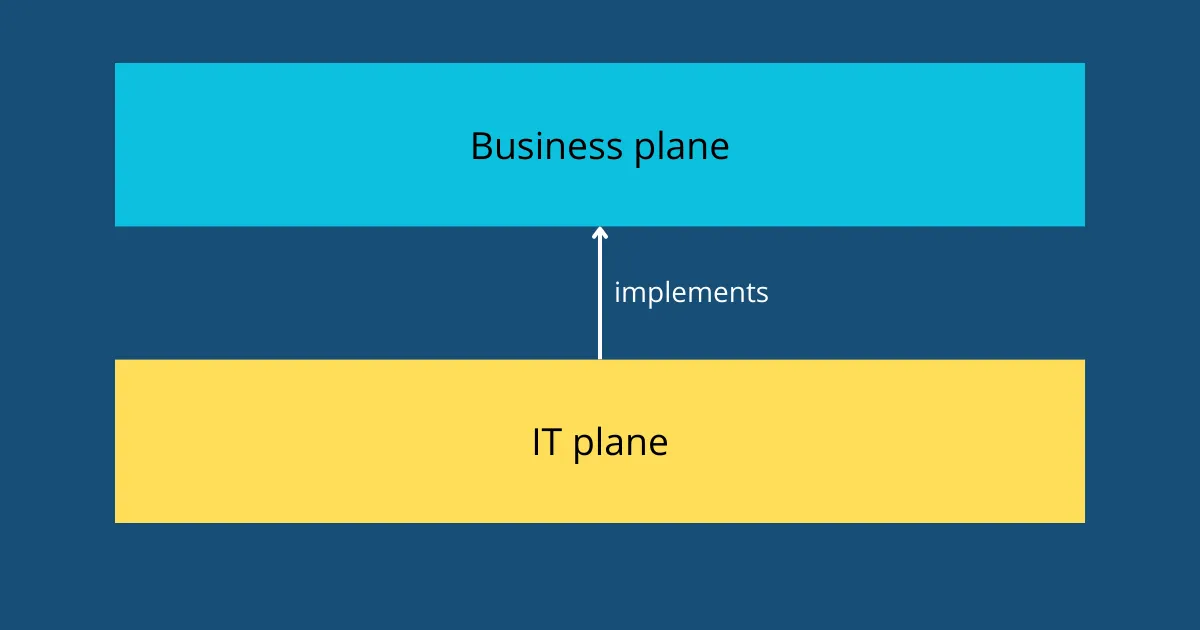

In my previous article about cross-domain collaboration, I showed the below image, which covers an important idea: the business plane is implemented by the IT plane, and thus in a majority of cases, the business plane should be understood independently of its (technical) implementation.

The reason that this is important relates to a central idea of design thinking1, where we first explore the problem space and only then go to solutions. By bringing talk about servers, APIs, and buttons into the mix too soon, we risk trying to make a solution before having a clear view of the problem. Naturally, discovering solutions can give us more insights about the problem that we did not identify beforehand. However, not taking the time to discovering the problem space at all may lead to solutions to a non-existing problem. After the problem space has been identified, there should be requirements that a solution has to fulfill in order to be successful. Only after going through this at least once and collecting some requirements, can we start finding a solution that fits these requirements.

What is more, discussing technical solutions may require knowledge that not all participants have. An involved salesperson can not be expected to understand the implications of different implementations to the same level as a developer or architect can, and a marketing manager may not immediately grasp all details of a set of C4 architecture model2. The same goes the other way of course; most developers are not marketing experts, and the combination of solution architecture and sales has not been super common either in my experience.

When discovering problems and solutions, I use facilitation techniques to guide multidisciplinary groups to answer the following questions in order:

What business outcome are we trying to achieve?

What important information, non-technical restrictions, and trade-offs should we consider for our solution?

What technical restrictions and trade-offs should we consider for our solution?

The first two questions focus solely on the business plane, and only after that do we move to restrictions existing in the IT plane. We need to account for these (we sadly live in the real world where we do have to consider the existing IT landscape), but only after first defining what we are doing in business terms.

The ‘old days’ frame

Even when explaining the importance of first talking about the problem space, it can happen in discussions that participants are still very solution focused. A helpful frame I have employed for this in the past is the following: “Imagine we are running this company in the year 1900. All we can use is humans who communicate and paper to administer things. how would you solve this problem?” To answer this question, problem solvers can not rely on the words that indicate a modern technical solution. Therefore they have to explain which roles and information is involved. This then opens up the conversation to steer back to what the actual problem is. Why do we need those people? Why is this information relevant?

Language management

The concept of ubiquitous language3 that is part of domain-driven design4 ties in with the point I am trying to make. Keep a glossary of terms and review or challenge the definitions in there once in a while to see if your local language is still sufficient for your goals. Bounded contexts5 describe a part of the business, so that a discussion on the backend does not have a domain model with sales terms included. Within a bounded context, explain the terms and their relationship to each other, preferably using a domain model. These domain models should be understandable for all stakeholders. If questions regarding the domain arise, a group of stakeholders can get the answers together.

Every once in a while, it may be helpful to pretend you are a new employee (or, way better, hire one) that asks of each term what they mean and how it relates to everything else. Let them read some onboarding documentation and then ask away in meetings. You will find out quickly what you have clear and which words still require an agreed-upon definition. You will also be confronted with the amount of abbreviations you use, as well as the vague English terms that can disguise real meaning (the last point mostly applies to companies where English is not the primary language, although English-speaking businesses may also use vague English terms).

In conclusion: language is at the core of communication and using it deliberately promotes shared understanding. By distinguishing the problem space from the solution space, there is more opportunity to focus on what we are really trying to achieve. Using deliberate language management techniques like domain modelling and creating a glossary, can improve a group’s understanding of said domain. Understanding is the basis on which results are booked.

If you have any thoughts on the article, I would love to hear them.

Additionally, if you would like to hear my future thoughts, consider subscribing to be notified when they form.